Lake Missoula / Scablands / Columbia Flood Basalt

Sacred Site Pilgrimage of the Epic of Evolution

report by Connie Barlow, 2005

THIS PILGRIMAGE wends through northwestern Montana, eastern and central Washington, and northwest Oregon. It is an opportunity to reflect on these realizations:

Catastrophes happen! Nature is not always a gentle breeze and fruit ripening on the vine. Devastation at scales unrecorded in written histories have happened — indeed, they will happen again. And yet . . .

Is this a universe we say "Yes!" to?

Catastrophes nevertheless engender opportunities for beauty, fertility, creativity because:

Emergencies lead to emergence; crises call forth creativity

Ideally, one begins this pilgrimage in western Montana, as Michael Dowd and I did in September 2005. The Missoula valley, the Bitteroot Valley south of Missoula, and in the National Bison Range Hills that rise above the valley of the Flathead River north of Missoula, all offer stunning examples (above photos) of lake terraces formed as Glacial Lake Missoula rose.

Ice Age "Lake Missoula" left terraces on these slopes near Missoula MT

There are lots of excellent websites with photos and maps that you can google on this topic. Two excellent, well-illustrated guidebooks for seeing and learning about features on this pilgrimage are:

Why did a vast lake rise in these valleys? Because a lobe of glacial ice advancing to the northwest blocked the Clark Fork River.Glacial Lake Missoula and Its Humongous Floods, by David Alt

Cataclysms on the Columbia, by John Eliot Allen

Each time the ice dam broke on Glacial Lake Missoula, a catastrophic flood would occur. This alternation between ice-dammed lake and flood happened repeatedly between 20,000 and 12,000 years ago. The water behind the ice dam would rise until it was high enough to float the ice barrier. When this happened, the dam catastrophically breached and all the water gushed out in a torrent over the course of perhaps 3 days. The maximum rate of flow during the breach is estimated to have been 10 times more volume than all the world's freshwater river flows combined!

2. Palouse Loess v. Scablands

LEFT: Scablands and giant pothole carved by catastrophic floods when Glacial Lake Missoula drained.

CENTER: Hills of windblown glacial silt provide rich farmlands in spots above the reach of flood waters.

RIGHT: Giant Erratic rock resting atop glacial outwash on a plateau northeast of Wenatchee.

The floods were so huge that they carved their own braided channels across the landscape of east and central Washington — but on a giant scale. Because the soil was stripped away in the last flood, which occurred just 13,000 years ago, these flood-scoured regions are collectively known as "The Scablands" (left photo). From an agricultural perspective, the land is too poor to support even grazing. But the scouring did create "potholes", again, on a giant scale, and these are superb waterfowl habitat.

Had the flood not occurred, a vast portion of central and eastern Washington State would now be as agriculturally productive as the Palouse Hills which escaped the flood in the southeast corner of the state. These hills are old dunes of vast expanses of windblown glacial silt, "loess" (photo on right). The Palouse Hills are today the best wheat-growing area in the country.

Catastrophe: some are swept away, some are unscathed; such are the workings of the world. In the above photo pair, both pictures where taken from nearly the same spot, but pointing the camera in opposite directions.

Coulees are gouged-out canyons in the high desert of central Washington that now carry little or no flowing water. The two most spectacular are Moses Coulee and, to just to the east, Grand Coulee. Both photos below are of Grand Coulee, and show the region known as Dry Falls.

3. THE GREAT COULEES OF CENTRAL WASHINGTON

We (Michael Dowd and Connie Barlow) visited Dry Falls on a cold, sunny day in early November 2005. The interpretive center was closed, and only a few other visitors lingered near the parking lot. We trudged off toward the setting sun, southwest along the top of the coulee wall, each of us finding our own spot to commune with the grand vista of cataclysm. We re-united along the top edge of the coulee wall just as the sun was setting over our right shoulders, each of us kneeling, murmuring a spontaneous, joint pledge to develop a new program facet of The Great Story: coming to terms with the shadow side of our evolutionary story, our evolutionary heritage — including the cataclysms. Just then, a coyote sang one long note from the direction of the sun. Then again, and again, five or six times. We rose and the chorus was over. And so was our pilgrimage to Dry Falls.

During the floods, water rushed out of what is now Washington State and its coulees, pouring through Wallula Gap where the Columbia River now meets the Oregon border. Some of the flood waters sloshed eastward up the Columbia and well into the Snake River, sculpting canyon walls there too. But all eventually rushed westward, carving out the Columbia Gorge with its spectacular hanging waterfalls. Curious: had these floods not happened, would the Columbia River today flow through a V-shaped canyon of volcanic rocks, as much of the Snake still does?

DANIEL DANCER (website www.inconcertwithnature.com) is a practitioner of sacred environmental arts who lives along the Columbia River. In his 2001 book of profound and deep ecospiritual reminiscences, Shards and Circles, he reflects on the Ice Age Floods while floating (in a wet suit) in the river, after a tugboat passes, hauling a barge of wood chips. This excerpt appears near the end of his chapter "The River Hoop":

During the final throes of the Ice Age, a little over 12,000 years ago, the Columbia took form with the catastrophic collapse of an enormous ice dam. The dam held back the waters of a vast inland sea known as Lake Missoula, and when it burst, waters exploded forth at a rate ten times the combined flow of all the rivers in the world! Over 2,000 feet high at its source, this towering mass of ice and water charged toward the pacific at nearly sixty-five miles per hour, scouring everything in its path into a maze of canyons and coulees visible from space. The event also created Dry Falls, the largest waterfall Earth has ever known. Recent studies of flood-deposited sediments suggest that the great flood occurred dozens of times, perhaps every fifty years or so until the climate stabilized. Geologists calculate that the approaching wall of water could be heard a good thirty minutes before it struck.

Great change indeed! I had imagined this event many times while standing on the cliffs near the River Hoop [the authors' work of environmental art, using found objects], but never while in the middle of the river. Surely hundreds of native people had witnessed the flood and died, but I wonder how many escaped to high ground and lived to tell the tale? I tried to picture a thundering wave, hundreds of feet tall, approaching me from behind. What a great death — to try to ride it! I could see the dunes near Squally Point and thought about the koan I had found there: "spare breaking." No way could such an event be spared! And the ice-dam broke again and again, creating the spectacular beauty that surrounded me. Was I living in the midst of a different kind of breaking? The Ice Age is a helpful metaphor for attempting to come to terms with the impact of our own "human flood." I thought of the Golden Prairie and realized again nature's cyclic patterns of creation and destruction that come in such astounding forms, and how they play — one upon the other — with divine chance and natural eloquence. Always beautiful. Always impermanent.

4. THE COLUMBIA RIVER GORGE

My mind drifted as a oneness with the river settled upon me. As the scent of diesel and chips dissipated, I began to think of the "great change" needed today and the spectacular natural event that had carved the Columbia River Gorge.

The last of perhaps a dozen flood events over the same landscape happened just 13,000 years ago, but the reason the landscape was plucked into cliffs and potholes was because of another catastrophe that happened 14 million years ago.

5. COLUMBIA FLOOD BASALT: an earlier catastrophe

Lava cooled quickly, cracking into columns, when the Columbia Flood Basalt poured forth 14 million years ago.

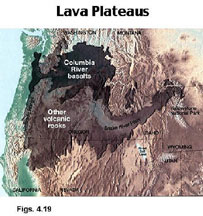

Fourteen million years ago, Earth opened in cracks in Idaho and eastern Oregon, pouring forth streams of basalt lava that covered much of the landscape. This was an oozing, rather than an explosive lava, called a flood basalt. No human ever witnessed a flood basalt in process. They are very rare events: the Deccan Flood Basalt in India probably was triggered by the meteor impact that wiped out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago. The Siberian Flood Basalt probably was triggered by an even bigger meteor impact that ended the Paleozoic nearly 240 million years ago. Our Columbian Flood Basalt is smaller in depth and area than the other two giants, and there is no particular evidence as to why it occurred.

Columnar basalt is exceptionally easy for raging currents and tornado-like whirlpools to pluck and erode away. It also makes for vertical escarpments, such as the cliffs along the gorge of the Columbia where a bridge carries traffic on Interstate 90. Downstream, the gorge continues, where the Columbia River (now a series of dammed reservoirs) demarcates the Washington/Oregon state boundary.

A finger of the Columbia Flood Basalt flowed 300 miles to the Pacific Ocean

at Lighthouse Point, north of Newport Oregon.

6. WILLAMETTE VALLEY: fertility owes to catastrophe

Thus, here in the Willamette Valley, one can abide in the hope that whatever the distress, the trouble in one's life or the world, surely there will be a rich possibility for growth — albeit impossible to conjure during the course of the dark time.

RETURN to the main page of SACRED SITES OF THE EPIC OF EVOLUTION

Home | About The Great Story | About Us | Traveling Ministry and Events

What Others Say | Programs and Presentations | Metareligious Essays | Writings/Rituals

Great Story Beads | Online Bookstore | Parables | Sacred Sites

Highlights of Our Travels | Favorite Links & Resources | Join Us! | WHAT's NEW?